Srijit Seal, PhD (Cantab)1

With contributions from Arijit Patra, DPhil (Oxon)2

1University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB3 9AL, UK

2University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK

What does the world need from science? Solutions to climate change, pandemic preparedness, healthcare inequities, and emerging global challenges require interdisciplinary collaboration and rapid innovation. What kind of scientific workforce does this require? Researchers need deep expertise but the ability and willingness to collaborate across disciplines, communicate effectively with audiences, work comfortably with uncertainty and rapid iteration, and distribute their talents across industry, government, NGOs, and startups, not concentrate in academia.

Yet our current PhD system optimizes for none of these critical needs. Instead, it emphasizes narrow technical depth over collaborative breadth, publication metrics over practical problem-solving, and academic career paths over professional outcomes. We're training scientists for a world that no longer exists while systematically excluding the diverse perspectives we desperately need. The tragedy isn't just who gets excluded; even those who complete our increasingly lengthy training pipeline are often prepared for the wrong purposes.

The problems run deeper than admissions. We're witnessing what could be called "late-stage" academic dysfunction: a publication system that incentivizes quantity over quality, impact metrics that distort research priorities, and now AI-generated papers flooding journals. These interconnected failures have been building for decades, but we've reached a tipping point where the entire system is actively counterproductive.

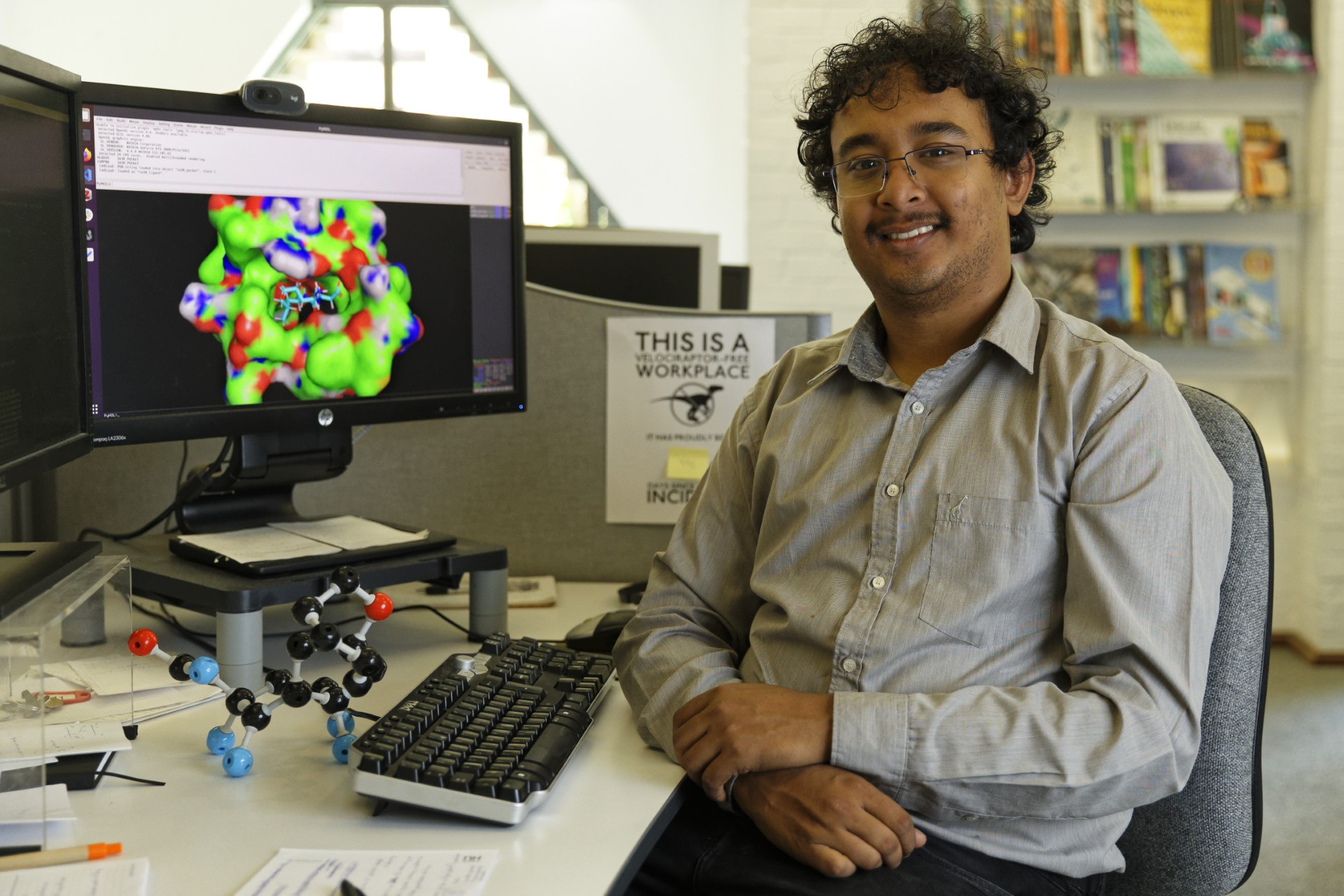

My experience reflects this broader breakdown. In 2018, admissions committees believed much more in potential over pedigree. My Cambridge scholarship came despite my thin research CV because someone saw promise in my passion for discovery. However, this holistic approach is becoming rarer, particularly in competitive US programs where quantifiable metrics slowly replace human judgment. The trend shows many students must now spend 2-3 years as research associates or assistants before applying to PhD programs. These positions in expensive cities like Boston, San Francisco, or London are de facto gatekeepers of scientific careers. Don’t have years of preparatory research experience? Many committees may not consider you.

Not all institutions follow this pattern; many, like Cambridge, have developed assessment strategies that heavily consider widening participation and avoid pure metrics-based selection. Many European systems maintain direct pathways from undergraduate to doctoral study. Some universities conduct entrance examinations focused on academic knowledge rather than research portfolios. Still, the trend toward increased barriers is spreading. Even institutions with traditionally inclusive approaches face pressure to adopt more "selective" criteria as competition intensifies and funding becomes scarcer. The variability between systems narrows as the dysfunctional model normalizes.

Prior research experience is valuable because it helps students understand whether they enjoy research before committing to a PhD. This perspective has merit — nearly 30% of graduate PhD students drop out [1], often after discovering they dislike the day-to-day reality of research despite being attracted to its ideals. However, this argument misses the distinction between providing research opportunities and requiring extensive research portfolios for admission. The solution isn't to demand two years of prior publications, but to create accessible ways for undergraduates to gain research experience: paid part-time positions during the semester, official course credit for research participation, and funded summer programs that don't require family wealth to access. The current system doesn't just require research experience but also the right kind of research experience, often from prestigious institutions, creating a multi-layered barrier that systematically excludes talented students from modest backgrounds.

How do we fairly evaluate intellectual curiosity, problem-solving ability, and resilience when AI can generate compelling personal statements and research proposals? This fundamental challenge is growing more severe as AI tools become sophisticated enough to fool admissions committees. Quantifiable metrics like publication counts can also be gamed and fundamentally favor wealthy students. Instead, we need assessment methods that are harder to fake. We need structured problem-solving interviews that ask candidates to work through novel challenges in real-time. Interviews need to focus on life story evaluations that assess how candidates made decisions and overcame obstacles with limited resources. Academic knowledge assessments need to test genuine understanding rather than research output. Collaborative exercises should evaluate teamwork and communication skills. Finally, pathway recognition should value students who worked multiple jobs, supported families, or took non-traditional routes to education. These approaches require more effort than scanning publication lists, but they're more likely to identify students with the qualities science needs.

The numbers tell a stark story. The median time to complete a PhD in the United States has stretched to 5.7 years in biological and biomedical sciences [2]. Adding 1-2 years of "pre-doctoral" research experience pushes the timeline towards a decade of financial instability. For comparison, where I trained, the British education timeline allowed me to complete a bachelor's, a master's, and a PhD in seven years, less time than many US students now spend on their doctorate plus preparation. This extended timeline fundamentally changes who can afford scientific careers. Students often graduate from college with debt, family obligations, and pressure to contribute to household income. The prospect of adding years of preparatory work followed by 6+ years of graduate stipends creates an insurmountable barrier.

Meanwhile, students who can afford to gamble on unpaid or low-paid research positions at prestigious labs can build impressive CVs while their parents cover living expenses. By the time they apply to PhD programs, they look like research superstars — not because they're more talented, but because they could afford to play the game. Professors who accept unpaid research assistants actively worsen this problem, especially when these positions are filled through personal networks. It is worth noting that many academics would not think twice before enabling such arrangements, driven partly by a paucity of funding mechanisms for such short-term visitors and partly by the lure of accomplishing tasks too sundry to waste the crucial hours of paid staff. This indirectly places a magnitude of responsibility on various funding bodies and institutional overlords of academia. Research consistently shows that professional networks are demographically homogeneous [3,4], meaning unpaid positions disproportionately go to students who share demographic characteristics with faculty members. This practice should be eliminated.

The rise of AI in research has intensified these problems. Labs now expect incoming students to have programming skills, machine learning experience, and familiarity with computational tools that didn't exist just a few years ago. Students with access to cutting-edge research experiences continue pulling ahead, while those without such opportunities fall further behind. Most (international) students cannot afford $60-80 monthly subscriptions to advanced AI tools, specialized online courses, or the computing resources needed for machine learning projects. I recently heard of master's students being rejected for lacking published papers in AI-adjacent fields. This requirement would have been absurd five years ago, but it is becoming normalized. The gap widens precisely when science needs broader participation most. AI tools could democratize research if properly deployed, but our current system uses them to create new forms of exclusion. In a sense, it appears that we are seeing an emergence of a vicious circle of supply-demand economics and the extreme competitiveness involved in securing fast-depleting research positions in top quartile universities.

The fundamental purpose of a PhD has been quietly changed. Doctoral education was designed as an apprenticeship in discovery where students learned to think critically, fail productively, and eventually contribute novel knowledge to their field. Students received modest stipends while learning, but not the same salaries for already-developed expertise. Today's committees want ready-made researchers. Academics, facing their productivity pressures, are less eager to invest considerable time training students who need to learn basic research skills. They want pre-trained candidates who can begin generating publications immediately. But here's the fundamental contradiction: if someone already has years of research experience and multiple publications, why do they need a PhD? We've created a system where the most qualified applicants are least in need of doctoral training, while curious minds who could benefit most from mentorship are systematically excluded.

Our current system may soon start producing increasingly homogeneous cohorts of researchers who can afford decade-long training periods but may lack the varied perspectives needed for transformative discoveries. Every brilliant mind we exclude from scientific training represents a lost opportunity for breakthrough discovery. Every student who abandons their research dreams for immediate financial stability is a tragedy not just for them, but for all of us who might have benefited from their insights.

The solution requires systemic change across multiple levels. At the institutional level, universities should eliminate unpaid research positions that create systemic and incidental barriers for students who cannot afford to work without compensation. Admissions processes should shift focus away from prior research output and instead emphasize candidates’ problem-solving abilities and intellectual curiosity. Structured interviews that assess how applicants approach unfamiliar challenges can offer a more equitable and insightful evaluation. Institutions should also prioritize recognizing qualities like resilience and resourcefulness over access to prestigious experiences. Across the broader academic system, we need to expand funded bridge programs that support students from underrepresented backgrounds. Increasing graduate fellowship funding is essential to reduce students’ dependence on individual lab resources for academic admission or survival. Publication and evaluation systems must also be reformed to reward the quality and impact of work rather than sheer volume or prestige. Importantly, the system should develop alternative, paid pathways for gaining early research experience. At the individual faculty level, it’s critical to refuse to accept unpaid research assistants and advocate within departments for more holistic admissions criteria. Faculty should also establish structures within their research groups that train and support students in developing the necessary skills, rather than expecting them to arrive fully formed.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the PhD's Purpose

The PhD admissions process has strayed from its original mission of training the next generation of scientific leaders. Instead, many programs now identify students who have received informal doctoral training. This represents a fundamental misallocation of resources when science needs to expand its reach and relevance.

Six years ago, Cambridge took a chance on a student with more questions than answers. That leap of faith led to research advancing my understanding of cheminformatics and drug discovery. But more importantly, it demonstrated that properly nurtured potential can produce outcomes that purely metrics-based selection may not achieve. How many future discoveries are we missing because we've forgotten that curiosity, not credentials, should be the price of admission to science? The next generation of scientific breakthroughs might come from the most unexpected places — if we're brave enough to let them in. After all, let us not forget the fundamental axiom that a doctor of philosophy would be moot without the idea of philosophy as a love for knowledge as an end in itself, enabling the joy of a limitless pursuit, and a training to foster a realization of the atavistic human desire for enquiry and curiosity. Chasing fictitious numbers and a forever pursuit of proper nouns and contrived accolades is not the best utility for bright young minds poised to change the world.

References

Council of Graduate Schools, PhD Completion and Attrition: Analysis of Baseline Demographic Data from the PhD Completion Project (Council of Graduate Schools, Washington, DC, 2022); https://cgsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/phd_completion_and_attrition_analysis_of_baseline_demographic_data-2.pdf.

National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Earned Doctorates (2023); https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/earned-doctorates/2023#survey-info.

Wapman, K.H., Zhang, S., Clauset, A. et al. Quantifying hierarchy and dynamics in US faculty hiring and retention. Nature 610, 120–127 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05222-x

K. L. Milkman, M. Akinola, D. Chugh, What happens before? A field experiment exploring how pay and representation differentially shape bias on the pathway into organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 1678–1712 (2015); https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000022.